Increasing participation and engagement in synchronous online meetings

As teachers increasingly adapt to the reality of remote learning and teaching, and adopt the technology and programs to allow for it, issues of accessibility, attendance and inclusion start to dominate discussion, even before curriculum is considered.

ACCESSIBILITY

Before a class meets in a synchronous online setting, there are issues of accessibility and inclusion. There are inherent inequities with internet access and strength, use of technology hardware, privacy concerns over a student’s home life being seen by the teacher and classmates, and access to synchronous meetings across different time zones. For the four issues, students at school will have access to the school’s internet and wifi network; they will have access to the school’s hardware such as laptops; they are separated from their home environment; and they will be in the class together. Once students are doing remote learning, generally from home, they may not have reliable internet, nor have appropriate hardware, nor have a quiet, private space to speak and listen, nor be in the same time zone (if international students have returned to their home country). Those issues must be addressed before considering how to increase engagement. But let us magically make those issues disappear. Each student has high-speed wifi, a fully functional device, has a quiet, private area to speak and listen, and can meet across time zones.

ATTENDANCE

Once the technical side of remote teaching is addressed, the students must then “attend” or log in to the synchronous meeting. Within the four walls of the classroom, a teacher already has the students present and hopefully, awake. By showing up at the door of the classroom, students, especially at high school, have either just arrived at school, or have transitioned from the previous class to the next class. When a class is conducted synchronously online, student attendance is not a given; a teacher sets the meeting time, logs in, and waits. While this is comparable to a teacher arriving at school, opening the classroom, and waiting, in-school attendance is monitored by school and district administration. Of course, nothing stops students from skipping class, but generally, the majority go to class. In the remote teaching environment that K-12 education operated in the Spring of 2020, attendance was not tracked nor reported. This is significant, as students connecting to synchronous meetings without accountability means that attendance, compared to in-school attendance, was lower. As of July 2020, attendance at in-school classes in British Columbia will be voluntary. Again, let us wave our magic wand and make attendance issues in synchronous meetings disappear. We may now address the issues of participation and engagement.

PARTICIPATION AND ENGAGEMENT

At the heart of participation and engagement in synchronous online meetings is the same premise that applies for in-class participation and engagement. Many strategies that a teacher uses to increase participation will work in both environments. There are of course, unique challenges to synchronous meetings, and those will also be addressed. In that light, the following strategies fall under two main categories: the first addresses strategies that would normally be used in the classroom and can be adapted to the synchronous online environment; the second are strategies unique to the synchronous online environment.

CLASSROOM STRATEGIES TO USE IN SYNCHRONOUS MEETINGS

- SOFT START – CHATTING BEFORE STARTING CLASS

In the classroom, students often enter, sit down, and chat with their neighbour before class begins. This creates a healthy conversation background buzz. In synchronous meetings, because only one person can talk at a time (the microphone cancels the use of other microphones), as soon as one person starts talking, everyone hones in on that person. This can discourage conversation when a student becomes the focus of attention. It also changes what the student says, excluding anything private like, “Hey Ralph, are you going to ask Betsy to the sock hop?” to become more general, “Hey Janie, I like your new bouffant hair style.”

Suggestion: Lead some of the conversation by connecting to individual students by asking some WH-questions. You may build in a routine such as pre-loading a slide that features a current event, cartoon, or trivia question to spark conversation in the minutes before class begins.

- GROUP OR PAIR WORK – BREAKOUT ROOMS

When teaching in class, a teacher may ask the class a general question and receive silence in response. The same happens in the synchronous online meeting. As most teachers know, there is safety in large groups; students can blend into the background by not saying anything. Just as in the previous scenario, a difficulty in class and in synchronous meetings is that once one person speaks, everyone’s focus goes to that person. Many students do not want to stick out like that.

Suggestion: To help encourage participation, a teacher in the classroom might split the students into small groups or with partners. The same may be done in the synchronous environment. That is, a teacher may use “breakout rooms” to manually or automatically split the class into groups or partners and have them virtually go into separate “rooms” to complete an assignment or have discussion. The teacher then has the ability to “check in” to each breakout room to see how the discussion is going, just as a teacher might wander from group to group in the classroom. You must know whether the application can support breakout rooms, as Zoom and Microsoft Teams allow for it, but Google Meet does not (at the moment).

- STUDENTS COMING TO THE BOARD – SCREEN SHARE

Demonstration of Screen Share in Zoom

In the classroom, teachers may have students participate by having multiple students write on the board to share ideas. The same can be done using the screen share option synchronously. Again, Zoom and Teams allow screen share, but Meet does not. Just as a teacher in the classroom must monitor what is written on the classroom board, in screen share, teachers must monitor and lay down ground rules before giving students the opportunity to share. The teacher must have oversight and control to delete or block student misuse of the app or platform if it arises. If that has been set, then students may use the screen share options to show others what they have done, and this gives students more control over the meeting.

STRATEGIES UNIQUE TO SYNCHRONOUS MEETINGS

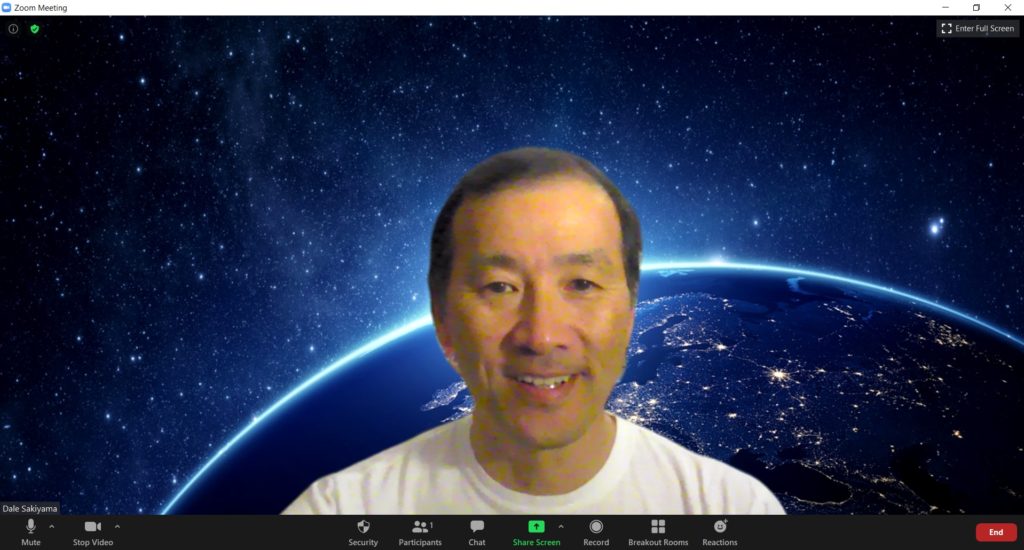

- BACKGROUNDS

Screenshot by Dale Sakiyama

In the classroom, students arrive “as is,” or already dressed for the day. In a synchronous meeting, they may not want to show their face or background. To encourage use of video, students may be more willing to enable their video if they may employ some anonymity through different virtual backgrounds or filters to alter their appearance. In Zoom, for virtual backgrounds users may upload an image from an online source, or from their own collection of images. Of course, teacher oversight of appropriate background images must be in place.

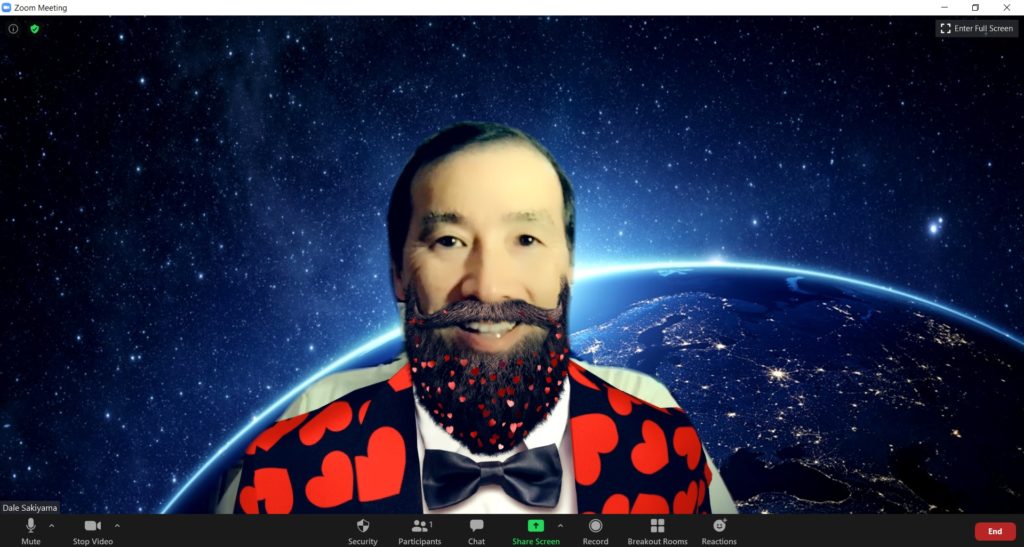

- FILTERS

Screenshot of Dale Sakiyama

For teachers who have not seen filters in use, for the past few years, Snapchat has offered users filters, which are typically animated additions to a user’s face in camera mode. As an example, a Viking helmet may be added on top of a user’s head. As the user’s head moves, so does the helmet. There are many options of filters a user might choose, so in a synchronous class setting, the teacher must set some parameters around what is acceptable. For use in Zoom, students may download the app from the Snap Camera web page, and then open the app to choose some favourite filters. Once chosen, the app must remain open for Zoom to connect to it. Once a Zoom meeting has been started, the student may change the video setting from the default webcam to the Snap Camera. Then the student should see the chosen filter applied, as will the rest of the students in the class.

These options are not guaranteed to get students to participate, but they may make it easier to engage in the synchronous setting. As with all strategies to try to increase participation and engagement, it is not a one-size-fits-all, and would require a teacher’s judicious use.

Critical Evaluation Framework

Using the CRAAP (Currency, Relevance, Authority, Accuracy, Purpose) Test, these suggestions meet the requirement for evaluating sources. First, the currency of sources is connected to research on engagement and online learning. The relevance is addressed in that it speaks to teachers during the pivot to remote teaching and learning. While part of the authority rests with the research articles referenced, authority also falls to me as a high school teacher experiencing the pivot to remote teaching in the present. Accuracy is only partially addressed by evidence and research, partly because some of the issues are so current that research has yet to be conducted. The purpose of the suggestions is to give teaachers some tools in the new remote teaching environment that may be with us for the foreseeable future. Even as medical changes occur to change the trajectory of remote teaching, there will be lingering shifts that will not return to education as it had been.

References

Hampel, R., & Stickler, U. (2012). The use of videoconferencing to support multimodal interaction in an online language classroom. ReCALL (Cambridge, England), 24(2), 116-137. doi:10.1017/S095834401200002X

Management Association, Information Resources. (Ed.). (2018). Student Engagement and Participation: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications. IGI Global. http://doi:10.4018/978-1-5225-2584-4

Sedivy-Benton, A. L., Fetterly, J. M., Wood, B. K., & MacFarlane, B. D. (2018). Using Creativity to Facilitate an Engaged Classroom. In Management Association, I. (Ed.), Student Engagement and Participation: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications (pp. 754-777). IGI Global. http://doi:10.4018/978-1-5225-2584-4.ch038

Leave a Reply