Photo by Dan Gold on Unsplash

To be inclusive can be described using multiple metrics. Generally speaking, in education that means all students with diverse needs have access to education. According to the government of B.C.’s section title, Inclusive Education Information for Parents, “Learning supports are resources, strategies and practices used so that all students have an equal opportunity for success at school. Every student deserves equitable access to learning, opportunities for achievement and the pursuit of excellence in their education (my emphasis). To make sure this is available to all B.C. students, services and resources are provided to students with various challenges, disabilities, talents or gifts.” (Education, n.d.)

Inclusion may also be interpreted separately from the educational terminology and thus be tied less to funding models and Individual Education Plans. That is, according to inclusionbc.org, that “Inclusive education is about how we develop and design our schools, classrooms, programs and activities so that all students learn and participate together.” (What Is Inclusive Education?, n.d.) This use of the word is how we are interpreting it, especially as it pertains to remote teaching and learning. For the two learning outcomes listed below, what follows are the explanations of how those outcomes relate to inclusivity, and the curated resources connected to the outcomes.

Learning Outcome: Support oral language practice synchronously while remote learning to address varying levels of Technology access, internet bandwidth, and time zones.

Photo by Dale Sakiyama

As much as remote teaching and learning has made teachers and students reimagine education, many of the difficulties identified by the switch to remote learning have roots in the same difficulties in face-to-face learning. When addressing an issue such as inclusion, there are comparable equivalents between remote and face-to-face learning. For example, where technology – or the lack of it – may exclude some students in the remote learning environment, the same may be said for face-to-face learning. That is, if a teacher asks students to use their phones to go out to take pictures of the school, some will not be able to do the activity because they don’t own a cell phone. The school may not have extra cameras to lend, and thus the student is excluded. In the same way, a student learning remotely may not have access to a camera to meet in a synchronous video meeting. How can this be addressed? Many school districts, such as Greater Victoria School District #61, implemented programs to loan technology to those students who requested. During the first month of remote learning in B.C., school districts scrambled to put these loan programs in place, using existing supplies of Chromebooks that school used for in-class instruction. The next challenge will be if or when a blended learning scenario happens. Can schools operate their in-class lessons with depleted supplies of Chromebooks that have been lent out? A finite number of laptops will see disparities in one place or another. The solution? Buy more laptops, which increases school budgets, which creates budget overruns.

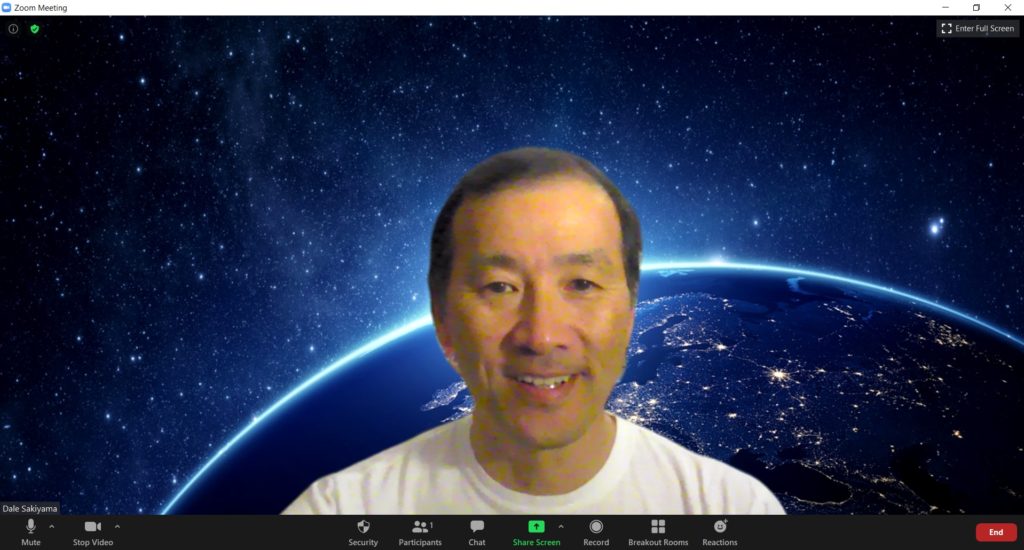

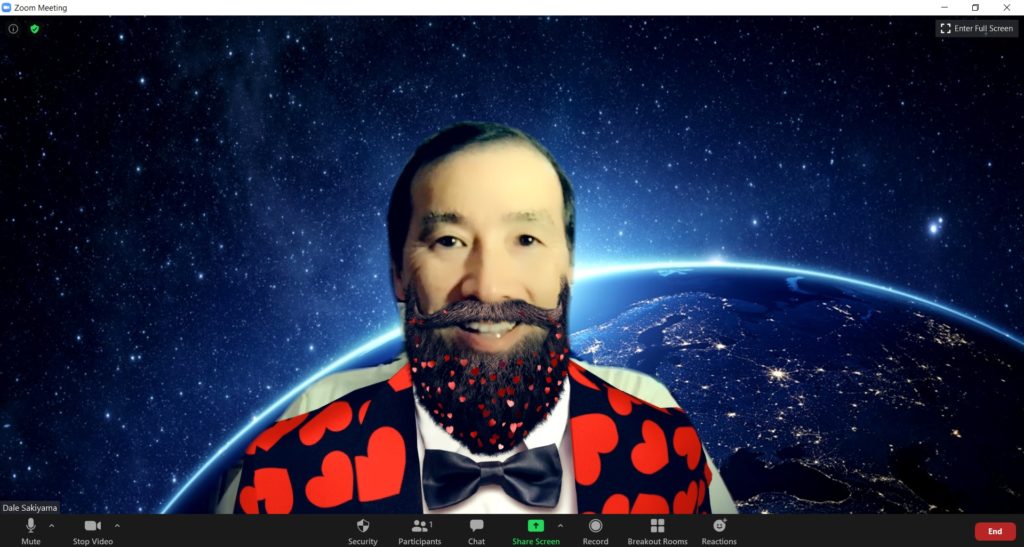

Photo by Dale Sakiyama

An additional source of exclusion during remote learning is unreliable internet capabilities. Some students do not have reliable internet access, and thus may not be able to download certain assignments like videos, or to stream content, or to connect to synchronous video meetings. The solution to this is not quite as simple as the school district loaning the hardware. When an in-class assignment would typically rely on live, instant assessment and evaluation, a teacher in the classroom has no barriers. In remote learning, students who do not have reliable internet access may not be able to do any of the activities that their peers can do. So how does a teacher make the activity more inclusive? It is not possible for a publicly funded school to ask families to make sure their privately paid Internet Service Provider is functioning at a high level. Since requiring students to regularly access the internet may exclude some, a teacher may need to ask those students to connect less frequently, such as once or twice a week. This may ease the notion of “missing out” of instruction or learning opportunities.

Photo by Luis Cortes on Unsplash

In extraordinary circumstances, international students may have returned to their home country, only to be not allowed to return. In such cases, synchronous video meetings may be difficult if, for example, a 10am meeting in BC is 2am in Japan or South Korea. To expect those students to be logging in to a meeting would be unreasonable. Yet how does a teacher account for time zone differences in a synchronous environment? There may need to be alternating meeting times, such as 10am and 6pm. This means that the teacher’s day does not end as it normally would, so compensating by shortening the length of the classes may ease the teacher’s load. Perhaps allowing those students out of the country to submit verbal responses via recorded video would be an alternative. While this does not allow for live, instant assessment, for the purposes of using the target language, it may be adequate.

Increasing Participation/ Inclusion for All

Once those factors have been dealt with, the second use of the word inclusion may be a barrier. The students at this stage are now in the synchronous meeting, but are not participating or engaged. How might a teacher include options for non-participants while adhering to learning outcomes? How might a student fulfill a learning outcome that includes oral participation? For simple oral participation in a lesson, one might argue that video is not necessary; that audio is all that is needed. This is true, as humans have for over a century gotten used to telephone conversations instead of needing to be face-to-face. At the same time, as teachers are also trying to build community in the class, finding ways to encourage audio and video participation in synchronous settings would help towards this goal.

Distracted Zooming. Photo credit: Dale Sakiyama

Resources to support synchronous video and oral language practice:

Synchronous Online Classes: 10 Tips for Engaging Students

Marie Norman, who wrote this article, is an associate professor in the School of Medicine at the University of Pittsburgh. While the article is aimed towards post-secondary instructors and students, many tips can apply to K-12. At the end of the article, Dr. Norman summarizes what is inherent in many of these kinds of teaching strategies articles (the citation is from her co-authored book):

“The tips offered here won’t miraculously eliminate the initial awkwardness of virtual class sessions, but they’ll help. And over time, the rhythms and idiosyncrasies of virtual meetings will become normal, even comfortable. What’s more, you’ll find that most of the tips provided here work equally well in a traditional classroom setting. They are simply methods for increasing mental engagement, participation, and accountability. Because, at the end of the day, teaching with technology is just teaching – if “just” can be applied to something as complex and nuanced as teaching. And while the contexts and specifics differ, the same learning principles and general strategies always apply (Ambrose et al, 2010).”

7 Strategies Designed to Increase Student Engagement in Synchronous Online Discussions Using Video Conferencing

Preparing for Fall 2020: Blended and Online Learning

Catlin Tucker is a speaker on education who has had classroom experience at the secondary level, but who now writes and speaks about blended learning. Dr. Tucker’s writing addresses the current coronavirus switch from in-class to online and blended learning, so there is acknowledgement of the added stressors of teaching in the typically uncharted territory for most teachers. In her article, “7 Strategies Designed to Increase Student Engagement…” her suggestions include ones similar to Marie Norman’s tips. As an example, Catlin Tucker’s strategy number two is, “Communicate your expectations for participation and behavior online.” Marie Norman’s tip number two is, “Tell students what to expect.”

As Dr. Tucker is a professional speaker and writer, she is also selling her knowledge. The second article, “Preparing for Fall 2020,” is an online course that people must pay to enroll in, in order to get detailed information from her posted outline.

Learning remotely when schools close: Insights from PISA

The

“This is not only a matter of providing access to technology and open learning resources, but will also require maintaining effective social relationships between families, teachers and students, particularly for those students who lack the resilience, learning strategies or engagement to learn on their own. Technology can amplify the work of great teachers, but it will not replace them.” (Learning Remotely When Schools Close: Insights from PISA, n.d.)

How can teachers and school systems respond to the COVID-19 pandemic? Some lessons from TALIS

“This crisis exposes the many inequities in our education systems – from the broadband and computers needed for online education, through to the supportive environments needed to focus on learning, and up to our failure to attract talented teachers to the most challenging classrooms.

But as these inequities are amplified in this time of crisis, this moment also holds the possibility that we won’t return to the inequitable status quo when things return to “normal”. We have agency, and it is the nature of our collective and systemic responses to the disruptions that will determine how we are affected by them. Our behaviour changes the system, and only mindful behaviour can avoid a breakdown of our education systems.” (Network, 2020)

References

Ambrose, S.A., Bridges, M.W., DiPietro, M. Lovett, M.C., Norman, M.K. (2010). How Learning Works: 7 Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Education, M. of. (n.d.). Inclusive Education Information for Parents—Province of British Columbia. Province of British Columbia. Retrieved July 19, 2020, from https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/education-training/k-12/support/diverse-student-needs/inclusive-education

Learning remotely when schools close: Insights from PISA. (n.d.). Retrieved July 21, 2020, from https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=127_127063-iiwm328658&title=Learning-remotely-when-schools-close

Network, T. O. F. (2020, March 23). How can teachers and school systems respond to the COVID-19 pandemic? Some lessons from TALIS. The OECD Forum Network. https://oecdedutoday.com/how-teachers-school-systems-respond-coronavirus-talis/

What is Inclusive Education? | Inclusive Education. (n.d.). Inclusion BC. Retrieved July 19, 2020, from https://inclusionbc.org/our-resources/what-is-inclusive-education/

Before starting, I give my students a handout that explains the guidelines around appropriate and inappropriate content, and how private or public the content may be. Once that is reviewed, I have them create a three-panel comic that describes three “bucket list” things they would like to do. That allows them to play with the features in the program before doing the main assignment, by altering clothing, hairstyle, body shape, and other features to create their “characters.” Of course, as with many projects, I show them my own examples to give them an idea what it might look like (without copying mine).

Before starting, I give my students a handout that explains the guidelines around appropriate and inappropriate content, and how private or public the content may be. Once that is reviewed, I have them create a three-panel comic that describes three “bucket list” things they would like to do. That allows them to play with the features in the program before doing the main assignment, by altering clothing, hairstyle, body shape, and other features to create their “characters.” Of course, as with many projects, I show them my own examples to give them an idea what it might look like (without copying mine). This digital storytelling tool addresses many aspects of

This digital storytelling tool addresses many aspects of  Powtoon is more focused on dynamic cartoon (although not exclusively cartoon) videos. As with all new resources, and especially digital tools, we try them out to gauge their effectiveness. The short example above was from a template that allowed me to change the character and text, although I stayed with the general storyline for the purposes of simplicity. The original template is below. Each has a limited option, free version, as well as upgrades to paid versions with more creative options. In the end, like most teachers, because I like to have as many arrows in my quiver, I put Powtoon into my folder of curated applications for possible future use.

Powtoon is more focused on dynamic cartoon (although not exclusively cartoon) videos. As with all new resources, and especially digital tools, we try them out to gauge their effectiveness. The short example above was from a template that allowed me to change the character and text, although I stayed with the general storyline for the purposes of simplicity. The original template is below. Each has a limited option, free version, as well as upgrades to paid versions with more creative options. In the end, like most teachers, because I like to have as many arrows in my quiver, I put Powtoon into my folder of curated applications for possible future use.

The major adjustment to make in our shift was that we had planned to use the film studio set-up at Spectrum Community School. We divided our responsibilities based on that configuration. To make the change to a video without face-to-face interaction required, again from BC’s Digital Literacy Framework, much creativity and innovation. Like everyone in the bigger world around us, we had to go with plan “B,” even though we had no plan “B.”

The major adjustment to make in our shift was that we had planned to use the film studio set-up at Spectrum Community School. We divided our responsibilities based on that configuration. To make the change to a video without face-to-face interaction required, again from BC’s Digital Literacy Framework, much creativity and innovation. Like everyone in the bigger world around us, we had to go with plan “B,” even though we had no plan “B.”

Recent Comments